The Infinite Canvas

The Role of Art As A Contemplative Technology

We have mistaken ourselves.

In our age of acceleration, we believe technology means silicon and code, that progress means optimization, that understanding means data. But there exists an older technology, one that predates language itself, that has always been humanity’s most sophisticated instrument for navigating the fundamental paradox of existence: how to live when everything we love is ever-changing.

This technology is art.

Not art as commodity or entertainment, but art as the primary method through which consciousness investigates itself. And at the center of this investigation lies a question so essential that every spiritual tradition and every great artwork has ultimately been an attempt to articulate it:

What is this force that moves through us, creating worlds upon worlds, even as it dissolves everything it creates?

The Vedic sages referred to it as kama, the cosmic desire that gave birth to the universe. Plato named it eros, the divine madness that drives souls toward beauty. The Buddhist teachings examine tanha, the thirst that binds us to suffering. But these are merely words pointing at something that resists all language, something that can only be known through direct encounter. And this is precisely where art becomes essential.

Consider what actually happens in the moment of genuine artistic encounter. Standing before Las Meninas, you don’t simply see Velázquez’s royal portrait; you experience the vertigo of consciousness observing itself observing. The painting doesn’t depict reality; it reveals the mechanics of perception itself, how desire constructs the very stage upon which experience unfolds. This isn’t interpretation. This is technology in its truest sense: a tool that transforms the user.

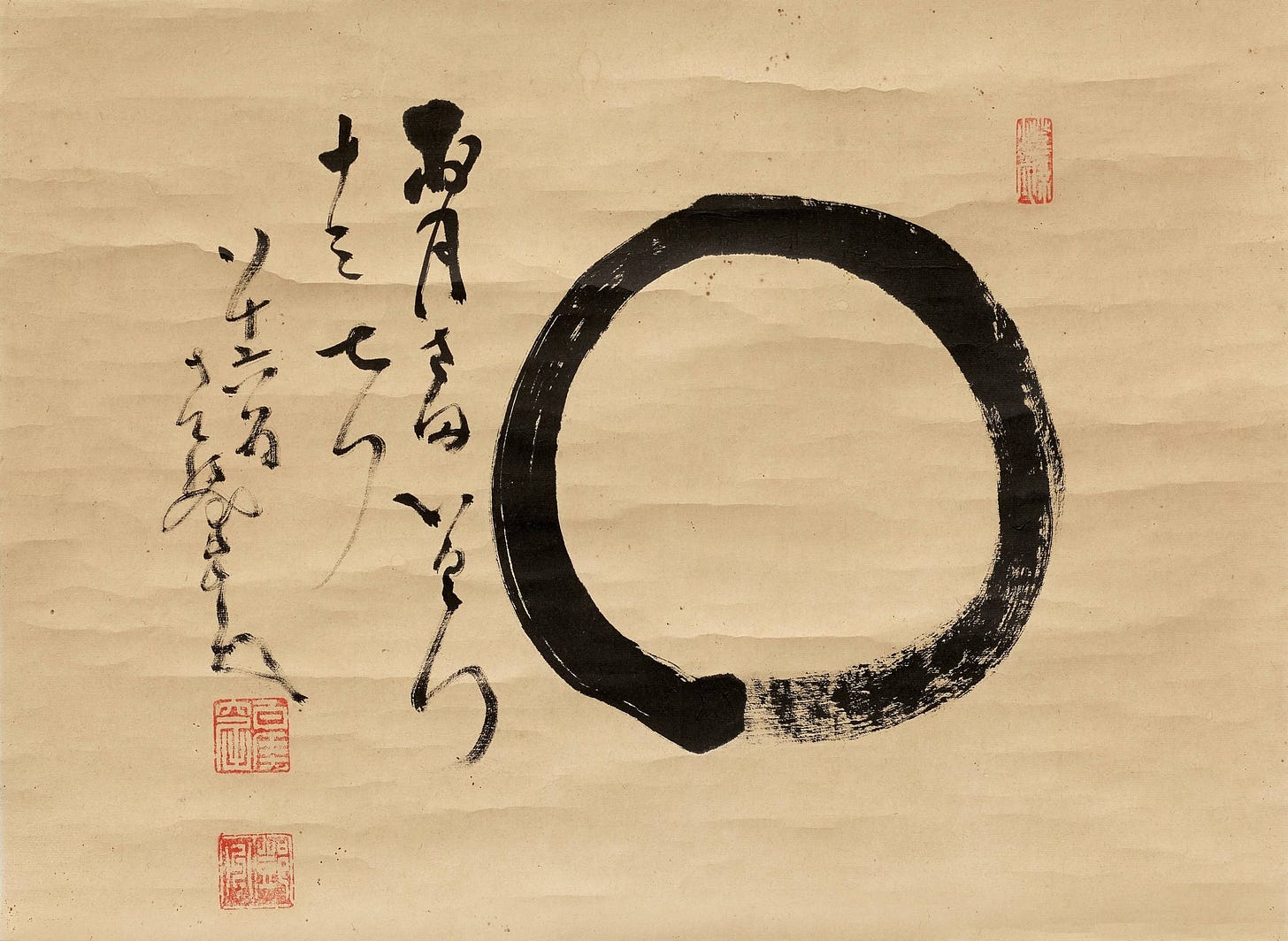

The great artist-philosophers understood this. When Hakuin painted his ensō circles, he wasn’t making decorative objects. He was creating devices for consciousness to recognize its own nature, empty and full simultaneously, forever completing a circle that has no beginning or end. When Agnes Martin drew her infinite grids, she wasn’t pursuing minimalism as style but as method. Each line became a breath, each canvas a demonstration that repetition itself is illusion, that no two moments are ever the same.

Here we arrive at the crux: Desire and impermanence aren’t opposite forces; they’re the same force experienced from different vantage points. Desire is how impermanence feels from the inside. Every creative act emerges from this recognition, whether conscious or not. The artist reaches for the brush precisely because the sunset is already fading. The poet breaks into song because silence is always returning. We make things because everything is always unmaking itself.

This isn’t philosophy; it’s phenomenology. It’s what you can verify in your own direct experience every time you feel the urge to photograph a moment, to write down a dream, to capture something, anything, before it dissolves. That catch in your breath when someone you love turns to leave the room, knowing this exact configuration of light and presence will never occur again. That impulse, that exact movement of reaching, is desire revealing itself as the engine of temporality. We don’t have experiences in time; desire creates time through its very reaching. Yet all of this movement occurs within the timeless space of awareness, like waves rising and falling in an unchanging ocean.

The contemplative traditions have always known this, but they’ve often positioned themselves against desire, as if liberation meant its cessation. Art offers a different proposition: What if desire isn’t the problem but a path? What if the very intensity of our longing, when fully met and genuinely expressed, becomes the doorway to understanding impermanence not as tragedy but as grace?

This is what Rothko knew when he said he painted “basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom.” He wasn’t depicting these states; he was creating technologies for their direct transmission. Stand before his Seagram Murals and you don’t think about mortality. You feel it in your cells. The painting doesn’t represent impermanence; it performs it, the colors literally shifting as your eyes adjust, the boundaries dissolving even as you try to fix them in perception.

But why does this matter now, in our current moment, more than ever?

Because we are living through the greatest crisis of desire in human history. Our technologies of distraction have become so sophisticated that we can indefinitely avoid the fundamental questions. We’ve created a world where desire is immediately satisfied by algorithms, where the ancient human experience of longing, that productive void that gives birth to art, philosophy, and spiritual seeking, is increasingly eliminated before it can even fully form. We’ve confused endless appetite with actual desire, mistaking the algorithm’s hunger for our own.

Yet paradoxically, we’ve never been more anxious about impermanence. Climate change, political instability, the acceleration of change itself: we’re surrounded by reminders of transience while simultaneously cut off from the tools that help us metabolize this truth. We scroll through infinite feeds trying to grasp something solid, but the feeds themselves are designed to never satisfy, to keep us in a state of aroused numbness that is neither true desire nor acceptance.

This is where art as contemplative technology becomes not just relevant but urgently necessary. We need practices that can hold complexity without resolving it, that can transform anxiety into inquiry, that can teach us how to desire beautifully in a world that is always ending.

The movement we need isn’t another school of art or another spiritual technique. It’s a remembering of what art has always been: humanity’s most sophisticated method for apprenticing ourselves to impermanence. Galleries can become mystery schools. Studios can become laboratories for consciousness research. Creative acts can become a practice of learning how to love, to be deeply intimate, with the preciousness of the present moment that fades.

This isn’t metaphor. This is protocol.

The artists who understand this are already creating the sacred technologies of the next era. They’re not creating objects to be consumed, but rather experiences that transform the experiencer. They understand that in our age of artificial intelligence and virtual reality, the most radical act is to return consciousness to its own depths, to remember that we are not users or consumers but consciousness itself, within which the creative principle arises and plays.

The canvas has always been infinite. The question is whether we’ll remember how to see it.

If this resonates, check out my recent contemplative art collection, Metabolize.

Emergence with Rachel Weissman is a weekly exploration of the interconnections between consciousness, technology, and planetary flourishing.

If you find this writing valuable, leave a heart ❤️, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.